La Cancha del Estado

Investigating El Salvador’s National Stadium and the Politics of Space

Exhibit Guide

This virtual museum examines El Salvador’s creation of a new multi-purpose national stadium (Estadio Nacional de El Salvador), replacing the national football team’s current stadium, Estadio Cuscatlán. Leading the public charge on this project is Nayib Bukele, El Salvador's president since 2019, known for his assertive leadership and populist appeal. Bukele, of Palestinian descent, began his political career as mayor of Nuevo Cuscatlán and later San Salvador, before ascending to the presidency. His tenure has been marked by a consolidation of power, with his party, Nuevas Ideas (New Ideas), securing near-total control of state institutions (Al Jazeera). In the broader political environment, Bukele has positioned himself as a disruptor of traditional politics, often clashing with established parties and institutions (Blitzer). By taking a hands-on role, such as laying the first stone in December of 2023, Bukele has intertwined his charismatic image with the national endeavour of creating Latin America’s largest stadium (El Salvador in English). Yet beyond its role as a sports venue, the new stadium is an ideological, political, and economic statement, reflecting Bukele and his government’s vision of modernization, nationalism, and global partnerships.

A spatial theory approach underpins this exhibition. This entails examining the stadium as a static space and as a site of ongoing political production, memory, and power. Drawing from Henri Lefebvre’s "Production of Space" and Andrew Smith’s concept of municipal re-imaging, this exhibit considers how stadiums are more than physical constructions, they are designed, contested, and experienced within political, social, and national frameworks. The location of the stadium on a former military academy grounds embeds it within a legacy of state discipline and control, raising questions about who has the power to construct national identity through space. At the same time, the replacement of Estadio Cuscatlán, a historic stadium with deep cultural significance, signals a shift in the national narrative, where modernization is prioritized over historical continuity.

Lefebvre prompts us to consider the constructed spatial order of our environments, and how they are shaped by ideology, power, and material interests. He labels this concept the visual-spatial realm (Lefebvre 312). Guiding this investigation is his conception of reduction, whereby the expansion of this realm overwrites the natural and historical spaces which came before it. In this sense, Lefebvre discusses reduction in a non metaphorical manner, and instead prompts us to consider the material destruction of spaces, the decisions made by politicians, and the consequential displacements and substitutions, such as gentrification and urbanization.

Andrew Smith’s concept of “sport reimaging” provides a valuable lens for understanding this shift. He argues that cities increasingly use sports infrastructure to project images of modernity, competitiveness, and renewal—particularly in post-industrial or politically transitional contexts. These efforts, he writes, are “essentially a discourse, grounded in neoliberalism… [that] perpetuates the notion that places are commodities”(Smith 219). In El Salvador, the Estadio Nacional functions within this logic as a symbolic tool used by Bukele’s administration to recast the nation’s image in line with a developmental narrative. Smith also warns that such projects often overshadow or erase existing cultural signifiers in favour of more “imageable” icons—spaces easily branded and circulated. The replacement of Estadio Cuscatlán, with its long standing social significance, exemplifies this dynamic, where memory and identity are subordinated to spectacle and state-driven symbolism.

This exhibit presents the findings of an Open Source Intelligence (OSINT) investigation, where the displayed pieces were uncovered by analyzing newspaper articles, state media broadcasts, social media discourse, and satellite imagery repositories. This exhibit seeks to uncover what this stadium represents beyond its physical structure by piecing together fragmented and often conflicting narratives.

The methodology of OSINT enables an investigative approach that differs from traditional historical or ethnographic methods. By utilizing real-time digital data, this project examines how public discourse is shaped, restricted, and controlled. OSINT allows for the tracking of government messaging but also reveals instances of censorship, social media suppression, and the erasure of critical voices. However, this methodology also has inherent challenges, such as government-aligned media shaping available data and social media discourse manipulation through bot activity and state propaganda. Click here to learn more about OSINT methodologies.

Rather than organizing this exhibit under a singular thematic focus, the investigation follows the logic of OSINT inquiry, branching outward from the stadium’s construction to explore interconnected narratives. This allows for a flexible, non-linear exploration of football’s political role in El Salvador. Nevertheless, recurring themes emerge:

The national narrative of progress, in which the stadium is framed as a symbol of development, modernization, and international recognition.

The control of public discourse, particularly how censorship, nationalism, and political messaging shape media coverage of sports and infrastructure projects.

The contested meaning of football spaces, where national stadiums serve both as sites of state ideology and as spaces of public resistance.

This virtual museum does not seek to provide a single, definitive narrative about El Salvador’s new national stadium. Instead, it follows an OSINT-based investigative approach, where seemingly unconnected threads are connected to reveal a broader story about how power operates through space.

Furthermore, this exhibit’s structure follows the narrative of the stadium’s construction. Firstly, we will explore the construction of the stadium, and the spaces the project will replace. Next, the stampede at Estadio Cuscatlán and the state’s reaction of censorship. And finally, the national and community reactions to the stadium’s construction.

Exhibit Section 1

From Kuskatan to Global Brand

Image Source: Tripadvisor, Google Images

As the new national stadium is aimed to replace the current venue of the Salvadoran national football team, questions are raised about what is being lost in the creation of new spaces. These include “Who is this space meant for?”, “Who gets to decide?”, and “What is the purpose of this space?”

The current venue’s name—Estadio Cuscatlán—is a name rooted in the Nahuatl language; derived from “kuskatan” meaning “place of jewels” (Tobar 54) . Through development, it is evident that a physical symbolic representation of pre-Columbian, Indigenous Salvadoran is being erased and overwritten in the attempt to achieve newfound national goals. Namely, the exclusive use of Spanish is representative of a broader goal to present El Salvador as modern and globalized. Thus, the new stadium’s name has effectively stripped the connection between the embedded meanings of physical space and historically marginalized populations in Latin America.

Examples of similar phenomena include the renaming of CDMX’s metro stations to Nahuatl names, such as Chapultepec Station referring to the word “grasshopper” (99 Percent Invisible). These initiatives often reflect an effort of reconciliation with the Indigenous population of Mexico and the historical repression they have experienced. However, in the case of the Estadio Nacional, an inverted process is taking place—whereby the goal of Bukele’s administration appears to neglect or perhaps even discriminate against the representation of Indigenous populations.

Exhibit Section 2

Progression in Progress: Three Visions

This exhibit presents three contrasting bird’s-eye views of the site of the new Estadio Nacional de El Salvador, each offering a different perspective on the stadium’s past, present, and future. The images highlight how space is presented and manipulated in both official and public narratives.

Left: A Satellite View (March 12, 2022) – Captured via Google Earth, this image predates construction, showing the Captain General Gerardo Barrios Military School, the site where the new stadium is now being built. The satellite image remains the most widely available view to the public, despite being outdated. As such, spatial realities remain obscured by a lack of updated or freely accessible imagery, making it harder for the public to verify government claims about progress.

Source: Google Maps/Earth Imagery - Imágenes Gobierno de El Salvador

Middle: A Drone Composite (Feb 27, 2025) – This image, stitched together from drone footage captured by the Nuestra El Salvador YouTube channel, provides a more recent depiction of the site. The drone footage shows a barren construction site, but the stadium is far from completion. The contrast between these first two images reveals the lag between public access to updated maps and the rapid physical transformation of space on the ground.

Source: Nuestro El Salvador Youtube Channel

Right: A Presidential Render (Nov 30, 2023) – The final image is a polished digital render released by President Nayib Bukele via X (formerly known as Twitter), projecting an idealized, futuristic vision of the completed stadium. The render suggests a near-utopian vision of modernization and development, a symbol of El Salvador’s supposed transformation under his leadership. This image, unlike the others, is not a representation of the present reality but of a political promise—one that has been met with both optimism and skepticism.

Source: Nayib Bukele Twitter (@nayibbukele)

Exhibit Section 3

Militarization of the Pitch

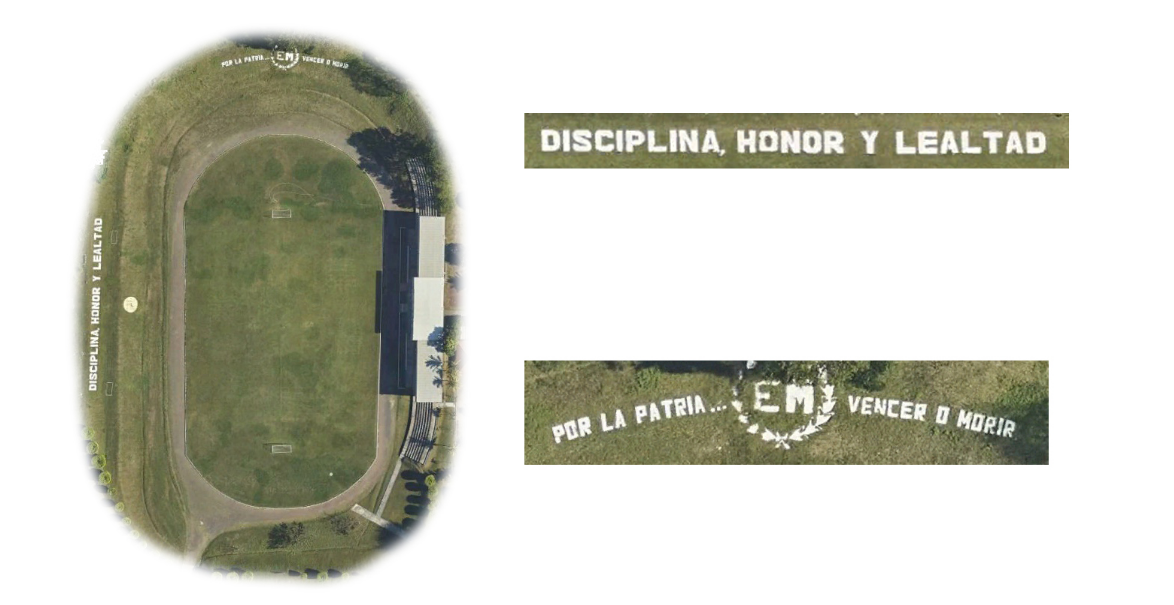

This image captures the former football field of the Captain General Gerardo Barrios Military School, now displaced to make way for the new Estadio Nacional de El Salvador. The field is marked by two phrases:

"Disciplina, Honor, y Lealtad" (Discipline, Honor, and Loyalty)

"Por la Patria – Vencer o Morir" (For the Homeland – Victory or Death)

These messages reflect how football, particularly in a military context, becomes intertwined with nationalism, discipline, and duty. In this context, sports fields are transformed into arenas of ideological reinforcement, where values of obedience, sacrifice, and national pride are instilled. The relocation of this field does not erase its significance; rather, it highlights how state narratives are embedded into the spaces where people gather, train, and compete. The question remains: How does this ideology carry over into the new national stadium?

Source: Google Maps/Earth Imagery - Imágenes Gobierno de El Salvador

Exhibit 4

Who is to blame?

A still image from a video uploaded to X (formerly Twitter) https://x.com/BabaGol_/status/1660204473459908610

In the interest of maintaining respect for the victims, the video is described below:

Clip 1: Spectators attempt to tear down a metal gate in the stadium to free those trapped behind it.

Clip 2: Spectators are dragging out either unconscious or deceased individuals. There are at least a dozen victims.

On May 20, 2023, a tragic crowd crush at Estadio Cuscatlán during a quarterfinal match between Alianza FC and CD FAS resulted in the deaths of 12 individuals and injuries to hundreds more. Initial reports predominantly attributed the disaster to unruly fans forcing entry into the stadium. For instance, the director of the National Civil Police, Mauricio Arriaza stated "between 400 and 500 people gathered [at the stadium]" and that the "eagerness to see the game" resulted in the stampede. (Muzaffar and Graziosi)

This narrative suggested that fan misconduct was the primary cause of the tragedy.

However, subsequent investigations unveiled a more complex and troubling scenario. Authorities arrested five football officials, including the president of Alianza FC and executives from EDESSA, the company managing Estadio Cuscatlán. Prosecutors accused them of greed and highlighted issues such as the sale of fake tickets and inadequate crowd control measures . The overselling of tickets and the failure to open sufficient entry points in a timely manner led to overcrowding and panic among attendees (Buschschlüter).

Amidst the chaos, spectators displayed acts of heroism that contradicted the initial portrayal of them as aggressors. Videos circulated on social media showing fans attempting to tear down metal gates to allow others to escape the crush and dragging incapacitated individuals to safety. These actions underscore the community's efforts to mitigate the disaster, challenging the narrative that solely blamed the fans for the incident.

The evolving accounts of the tragedy highlight the challenges in constructing an accurate narrative. While there is a legitimate concern about potential government suppression of information, the situation is further complicated by the emergence of varying reports and interpretations over time. This exemplifies the importance of critical analysis and the need to consider multiple perspectives when examining such events.

Exhibit Section 5

Esmeralda Monteagudo

A video of a medical intern apologizing for comments made on Twitter in the aftermath of the 2023 stampede at the Cuscatlán stadium, the current home of the Salvadoran national football team. The stampede occurred partially due to occupancy issues, highlighting the need for larger stadiums such as the one undergoing construction. Victims arrived at Rosales hospital the night she and several other medical students complained about working conditions (specifically, the capacity of the hospital), a post which is now scrubbed from the internet. News coverage of this incident never states the exact comments she made.

In retaliation, Monteagudo and the other students were suspended from their duties by the Ministry of Health and Salvadoran Social Security Institute. Responding to these actions, the Medical College deemed them arbitrary.

This incident illustrates how the state manages public narratives surrounding national infrastructure, particularly when symbols like Estadio Cuscatlán become sites of tragedy and critique. The intern’s now-removed post reflects a moment where the limits of both stadium and hospital capacity collided—revealing infrastructural strain rather than national strength. The government's swift disciplinary response, paired with the erasure of the original comments and the media’s omission of their content, suggests a broader effort to suppress dissent that complicates official portrayals of progress. Rather than acknowledging systemic shortcomings, the state redirects attention toward the promise of future development, embodied by the new stadium. Thus, national projects are not just built environments but also curated narratives, shaped through both material construction and controlled discourse.

The disciplinary actions against Monteagudo and her colleagues triggered significant backlash from the medical community, who viewed the sanctions as unjust and politically motivated. The president of the Medical College publicly stated, “According to the head of the Medical Association, there is no reason for a sanction,” asserting that the government's response lacked legal justification. Another representative added, “Civil Service has not found a cause, so they transfer the case to another chamber to prevent the person from being reinstated and enjoying their rights”. (Both of these quotations were translated from Spanish to English) (Ábrego)

These reactions underscore a broader context in El Salvador, where dissent is frequently managed through institutional silencing and bureaucratic deflection. Under Nayib Bukele's administration, the centralization of power and erosion of judicial independence have created conditions where state censorship—especially of public criticism—can be swiftly enacted without accountability. This incident fits into a regional pattern: in several Latin American countries, public institutions are increasingly used to suppress opposition under the guise of order or professionalism. Here, the state’s effort to discipline critical medical voices reflects a larger strategy of narrative control, where censorship becomes a tool to defend symbolic national projects and mute structural critique.

Exhibit 6

A Public Outcry

https://x.com/Noalospoliticos/status/1661458716397301764

https://x.com/ReneCruz73/status/1661562498519007234

https://x.com/achelemus5/status/1661752882822094848

https://x.com/Izalco1980/status/1661590764919619586

Following the suspension of the doctors involved in commenting on the 2023 Estadio Cuscatlán stampede, public backlash erupted across social media, revealing a striking dissonance between the official narrative and popular sentiment. The government's actions, framed as professional disciplinary measures, were widely perceived as punitive and politically motivated. A wave of tweets emerged not just in defense of the medical students, but as broader indictments of how the Salvadoran state handles dissent—particularly when it intersects with national tragedy and symbolic infrastructure like the national stadium.

One user, Francisco Menendez, condemned the media’s complicity in scapegoating the students, writing, “It is a SHAME that the media is blaming these poor students for the deaths in the Cuscatlán stampede... meanwhile FESFUT/CLIMA/EDESSA are perfectly calm.” His comment exposes a common strategy in state-aligned media ecosystems: the redirection of blame away from institutional power toward individuals with limited authority. Another user, René Cruz, took aim at the hypocrisy of the disciplinary action, noting that if President Bukele fired every staff member who made a mistake, “she [Monica Ayala, head of the ISSS] would no longer be director.” With biting sarcasm, he concludes, “EMPATHY is a great value!”—underscoring the double standards within the government’s own apparatus.

Others, like Carlos Hermann Bruch, shifted the conversation toward professionalism and respectability, questioning whether the suspended women were upholding the values of the medical profession. “I’m surprised the president doesn’t encourage them to respect the profession more... and above all, their patients,” he wrote. Though framed as a defense of patients, the comment reveals how appeals to institutional decorum can be weaponized to delegitimize dissent.

Together, these posts illustrate how digital platforms have become contested arenas for truth-making and counter-memory in El Salvador. While the state seeks to manage the narrative surrounding national development—portraying the new stadium as a solution to past infrastructural failures—citizens use social media to document what official records omit: discontent, contradiction, and hypocrisy. Within the OSINT methodology of this exhibition, these tweets function as evidence of how dissent is both punished and resisted. They show that infrastructure projects like the Estadio Nacional are not merely physical interventions, but politically charged symbols whose legitimacy must be constantly defended through censorship, disciplinary action, and narrative control.

Exhibit Section 7

Diplomacy, Debt, and Dissent

Three contrasting perspectives on the construction of Estadio Nacional de El Salvador, illustrating how the project is entangled in diplomatic ambition, public scrutiny, and economic anxieties. At the groundbreaking ceremony, President Nayib Bukele, standing alongside Chinese Ambassador Zhang Jianwei, declared that the stadium would be a “cathedral of sport” and a testament to the friendship between El Salvador and China. Public discourse on social media has gone further, with critics arguing that the stadium is not a gift but a vehicle for deepening economic dependence on China. One post speculates that gold mining rights will be granted to Chinese companies in exchange for the project, calling it part of the “China Debt Trap.”

El Salvador’s deepening ties with China have accelerated since Bukele severed diplomatic relations with Taiwan in 2018, a move that opened the door to large-scale infrastructure promises under China’s Belt and Road Initiative. The stadium is one of several major projects China has supported in the country, including a library, water treatment plants, and a new national pier. Critics argue that these projects, though framed as “gifts,” mirror China’s broader foreign policy strategy of leveraging soft power and infrastructure diplomacy to gain economic and political influence in strategically positioned developing nations. In this context, the stadium becomes more than a bilateral token—it becomes a node in a larger geopolitical network of influence, where national symbols are embedded within global ambitions.

By invoking the language of sanctity, Bukele elevates the stadium beyond mere infrastructure, framing it as a sacred space of national unity and international prestige. Describing it as a “cathedral of sport” situates the stadium within a tradition of political speech that sacralizes national projects to evoke collective belonging, pride, and moral legitimacy. In El Salvador—where the Catholic Church and sacred imagery remain potent forces in public life—this rhetorical strategy resonates strongly. It reframes a Chinese-funded mega-project not as foreign intervention but as a sacred national endeavour. The stadium becomes a place not only of athletic competition but of spiritual and cultural consolidation, where the state and its global partners present themselves as stewards of the national good.

This official narrative, however, is met with skepticism. The president of CESTA—an environmental organization, Ricardo Navarro, has criticized the necessity of another stadium, raising concerns about the ecological impact and government priorities. While there is no public evidence that Navarro has faced censorship or retaliation for these remarks, the absence of such reporting should not be mistaken for proof of safety or impunity, particularly in a media environment marked by increasing state influence. Notably, Navarro has a history of engaging critically but constructively with the Bukele administration. In one interview, he stated that if Bukele’s mining ambitions could be done ecologically, “I would support it”. His more tempered stance compared to other activists may offer him a degree of political space, yet it also underscores how precarious dissent can be in contexts where the boundaries of acceptable criticism are increasingly shaped by the state.

Exhibit 8

A Bird’s Eye View

(Image and data sources captured via EOS Data Analytics Landviewer)

The image above is a false-colour composite captured by the Sentinel-2 Satellite on April 13, 2025, covering a 5 km² area surrounding the Estadio Nacional construction site. This visualization uses shortwave infrared (SWIR) and near-infrared bands (B12, B11, and B04), which are especially sensitive to changes in vegetation and built environments. In false-colour imagery, healthy vegetation typically appears in shades of deep red or magenta, while built-up areas and disturbed land—such as roads, concrete surfaces, or cleared construction zones—show up in bluish or greyish tones. The image reveals a prominent zone of disruption and spectral dullness at the centre of the frame, where the stadium is located, suggesting significant vegetation loss and land clearing as part of the ongoing construction. This method of satellite analysis is a powerful tool for identifying rapid infrastructural change and its ecological impact.

The second visual—a time-series graph of NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) values—offers a longitudinal perspective on how development has reshaped the ecological profile of the 5 km² area surrounding the Estadio Nacional construction site. NDVI measures vegetation health by comparing light reflected in the near-infrared and red bands. High NDVI values (closer to +1.0) suggest dense, healthy plant life; low values indicate degraded, sparse, or non-existent vegetation, often correlating with built infrastructure or land in transition.

This dataset reveals a clear inflection point beginning in early 2023, when vegetation density drops sharply—coinciding with the initial stages of stadium construction. NDVI values decline from approximately 0.46 in early 2022 to below 0.42 by February 2023. While a modest rebound occurs by late 2023, the recovery remains incomplete, and a small dip reappears in early 2025. These fluctuations suggest sustained environmental disruption and a gradual—but not total—loss of green coverage. While some seasonal variation is to be expected, the deviation from past years indicates a structural shift in the land's function, likely driven by clearing, grading, and construction operations.

Beyond the ecological readings, this data raises deeper questions about spatial politics, accountability, and visibility. Development projects—especially those with symbolic or nationalist weight—are often accompanied by highly curated public narratives that emphasize renewal and modernization while downplaying social and environmental costs. The stadium’s construction has been heavily promoted by the Bukele administration as evidence of national progress and global integration. Yet remote sensing technologies like NDVI allow us to see past official imagery, offering an alternative layer of truth-telling that is difficult to refute or suppress.

These tools are especially vital in contexts like El Salvador, where dissenting perspectives are often minimized, censored, or erased from public discourse. In contrast to news reports or government press releases, NDVI data is empirical, impartial, and repeatable—allowing researchers, activists, and citizens to track changes over time and cross-reference them with official timelines. In this way, NDVI and other forms of spatial analysis become part of a broader investigative toolkit, aligned with the exhibition’s OSINT-based methodology. They allow us to pose crucial questions: What does development erase? Whose voices are left out of the national vision? And how can we document truths that institutions may prefer remain unseen?

Works Cited

Ábrego, Alma. “Reinstalan a una de las doctoras que se quejaron en redes sociales por la tragedia del Cuscatlán.” La Noticia SV, 5 July 2023, https://lanoticiasv.com/reinstalan-a-una-de-las-doctoras-que-se-quejaron-en-redes-sociales-por-la-tragedia-del-cuscatlan/.

Al Jazeera. “El Salvador's President Nayib Bukele cements power as he begins second term.” Al Jazeera, 1 June 2024, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/6/1/el-salvador-president-nayib-bukele-cements-power-as-he-begins-second-term? Accessed 13 April 2025.

Blitzer, Jonathan. “The Rise of Nayib Bukele, El Salvador's Authoritarian President.” The New Yorker, 5 September 2022, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2022/09/12/the-rise-of-nayib-bukele-el-salvadors-authoritarian-president? Accessed 13 April 2025.

Buschschlüter, Vanessa. “El Salvador's Alianza: Football club punished for stadium crush that killed 12.” BBC World News, 23 May 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-65683147. Accessed 13 April 2025.

El Salvador in English. “Nayib Bukele Lays Foundation Stone for El Salvador’s National Stadium.” El Salvador in English, 1 December 2023, https://elsalvadorinenglish.com/2023/12/01/nayib-bukele-lays-foundation-stone-for-el-salvadors-national-stadium/. Accessed 13 April 2025.

Lefebvre, Henri. La producción del espacio. Translated by Emilio Martínez, Capitán Swing Libros, 2020. Accessed 13 April 2025.

Muzaffar, Maroosha, and Graig Graziosi. “At least 12 dead and nearly 100 injured in stampede at El Salvador stadium.” The Independent, 21 May 2023, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/stampede-el-salvador-football-stadium-b2342833.html. Accessed 13 April 2025.

99 Percent Invisible. “The Art of the Olympics.” 99% Invisible, 30 July 2024, https://99percentinvisible.org/episode/591-the-art-of-the-olympics/. Accessed 13 April 2025.

Smith, Andrew. “REIMAGING THE CITY: The Value of Sport Initiatives.” Annals of Tourism Research, vol. 32, no. 1, 2005, pp. 217-236. ScienceDirect. Accessed 13 April 2025.

Tobar, Luis Antonio. Toponimia nahuat de Cuscatlan. Editorial Universitaria, 1961. Academia.edu, https://www.academia.edu/120545514/Toponimia_nahuat_de_Cuscatlan. Accessed 13 April 2025.